Chevaliere D’Éon is a special case in trans history - she is the first trans woman we really have a wealth of images of. Particularly amazing given we’re talking about the 1700s, just under 300 years ago and just under 100 years away from photography being invented

There are so many portraits, engraving and satirical cartoons of her but from what I can see none of them have ever really been catalogued and studied in a way that makes sense to trans ppl or a transgender history (or maybe they have and i’ve just not found that yet 🤷♀️ hmu if u have done this tho cuz we should talk). This is probs due to the overwhelmingly cis lens which she is viewed, so lets try to fix this a little for ourselves and explore some of the many faces of Chevaliere D’Éon

Before we get into it i do wanna say that no we can never know exactly how she identified in her own head cuz without a oujia board and the Most Haunted team we will never fully know, but with that being said she wrote an awful lot and mostly referred to herself as a woman so thats really how we should continue talking about her. Yes even if ur referring to her before she transitioned, if ur doing anything other than that then ur probably not as nice a person as u think u are.

It is baffling how she has literally written that she is a woman in her own words and cis historians will still stand there hands on hips saying ‘we just don’t know!’

So lets get into it and we’ll try and go in some sort of order

There are far fewer pre-transition portraits of D’Éon than after she had transitioned and tbh i was hesitant to show any but i think in order to understand what is going on we do need to look at some and also she was very fond of wearing her dragoon uniform maybe its what she would have wanted

1: Chevalière D’Éon by Francois Xavier Vesper - 1764

So here we have the earliest definite portrait of her by Francois Xavier Vesper in 1764, one year after she negotiated peace with England and she was living here.

We can see her here in her dragoon’s uniform with her cross of St. Louis displayed almost centrally, not quite tho. She is depicted wearing a tricorn hat with a rosette which wouldn’t have been the hat that went with the uniform, but maybe she did wear this? It could be that she was wearing this as it was more lightweight 🤷♀️

We can’t see much of her hair under the hat but the bit we can see i would say she is wearing it in the style u would expect someone of her station at that time. She has thin arched brows and her nose has a very thin, straight bridge but is a bit pudgy at the end. Her neck is covered by a very close collar (oh girl we’ve all been there…). She’s not drawn in a particularly masculine of feminine way and even the dragoon uniform doesn’t make her look overly gendered, tbh i get the feeling she liked the dragoons uniform for its display of class and her station rather than any gender presentation.

So now we have an idea of what she is supposed to look like let’s look at the others

2: Chevalière D’Éon by Thomas Burke - 1771

This portrait by Thomas Burke is dated 1771, the same year the Leeds Intelligencer (what became the Yorkshire Post) reported she was indeed a woman.

The text under the portrait itself translates as ‘after a portrait by Huquier’ who we know is James Gabriel Huquier. He drew the original sketch in pastels, which would then have become what we see here, the engraving by Burke.

This portrait is from a different angle to the last so a direct comparison is not as simple, however we can see that the nose is similar to before being thin and straight, but her chin is more protruding here. She has no hat which gives us a rare look at her hairline which looks alike the previous portrait tho it could have been a widows peak before some receding took place. She again is shown wearing a very close collar.

The most important thing to point out i feel is the lack of her medal! She was extremely proud of this and was rarely, if ever, seen without it.

3: The Rape of Miss D’Éon from France to England - 1771

An important note here is that rape does not mean what it does now. In this context it means kidnap.

The interesting thing about this portrait is that it refers to her as Miss D’Éon in 1771 which is before most cis sources report her as ‘living full time’.

This is a much more romanticised depiction and is part of a series of satirical cartoons that as far as i can see aren’t attributed to any artists in particular. I’ve included this and other satirical prints as I feel like its important to consider them as part of the canon of depictions of D’Éon - she was a celebrity of the time and more importantly she was a spy so having depictions that weren’t an exact likeness is probably helpful.

It is also important to remember that all portraits, whether satirical or not, at this time were very much propaganda - how D'Éon is depicted is no exception in any of her portraits.

In this etching she is being carried on the back of (Father) Time who is about to deposit her onto a British flag being held by 4 satyrs. What a meme!

The British Museum immediately note that she is wearing jack boots (military boots) before they say anything else about the image which feels so weird but obvs not as weird as misgendering someone literally being called Miss D'Éon in the print’s title.

She’s here wearing another tricorn hat with her uniform but this one has a frilly little bow on it which i guess is an attempt to feminise her. We again see no medal displayed which may be English artists not knowing how important that is to her.

By this point she had been living in England for almost a decade so this was not depicting recent events, but as she was gaining clout the ppl will have wanted to know more and in 18th century newspapers were the twitter of the time. Speaking of time, he is carrying D’Éon on his back probs showing how time is of the essence to kidnap her to save her from being chucked in the Bastille by Louis 15th, which would have been the end of her as shown by the inclusion of the scythe as death symbolism. This could also be symbolising a harvest tho?

One of the satyrs is wearing a barristers wig showing that the legal system was waiting to embrace her and protect her 🤢 and the one next to him has the cap of Liberty on a stick symbolising her freedom to come. The most interesting satyr tho is to the right and is wearing a low cut bodice. This is interesting cuz satyrs are rarely depicted as feminine and this could be a symbol of her being transgender, and honestly what trans woman hasn’t felt like a hairy little goat girl in a low cut bodice at least once in their life so yeah its a fuckin mood.

4: Stockbrokers Outwitted - 1771

Next up is satirical print for either the same series or a similar one and i can’t quite tell cuz they’re both anonymous but this one is less romanticised so it could be by a different person and a different series.

This is her going to see the brokers of the London Stock Exchange who had opened a betting pool on her gender 😫 grim i know. They were fully prepared for her to reveal her gender and were making plans accordingly but she turned up and said no and walked off, which isn’t really outwitting but good for her. We can see her here in her dragoons uniform that she was so fond of but again no medal yet she does have a tricorn hat on, this time with feathers or frills or whatever it was, which again was just a display of status and wealth, which u would deffo want to show if u were off to London Stock Exchange.

We can’t really compare facial features on a small print like this but we can see a straight, thin nose and protruding chin and arched brows.

The print depicts the whole debacle as a scheme she was in on, which is not a version of events I had not seen before and part of me is like ew how transmisogynistic and a part of me is just like yeah get it gurl u scam those men

5: The Discovery of a Female Freemason - 1771

This is the first portrait we get of her dressed femme and is called The Discovery of a Female Freemason. There is no artist attributed to it but it was published by Samuel Hooper, who published prints of a variety of things from Kirkstall Abbey to Marie Antoinette.

We see here her dragoon uniform has been carefully laid aside and she is now wearing the fanciest dress she is ever depicted in. On it we can see the Freemasons logo emblazoned as well as the cross of st louis on her breast.

She is wearing a headwrap/bonnet, which becomes a staple of most femme D’Éon portraits from this point onwards. Her hairline that we can just about see below the wrap is straight and flat, which is different to the last portrait which had her hairline exposed. The hairstyle remains the same tho with those side curls. Her eyebrows aren’t very arched here either and her chin is less protruding.

Overall she has a very soft and feminine look, which i would suggest was to show her in a very positive light. She has one large pearl earring on display which is giving girl with the pearl earring vibes and making ppl think of that image would deffo be one way to show femininity.

The text below the original print refers to her as “Lady D’Éon” and lists her many roles and accomplishments. The British Museum suggests she is in a very masculine pose which makes absolutely no sense as nothing about that pose says butch queen.

The busts and portraits around her are relating to hoaxes and tricksters of the time which insinuates that she had been lying about her gender in some way which is a really transmisogynistic narrative 🤢

Its unlikely that she would have posed for this as it is a satirical print. In fact I doubt she would have sat for most of the portraits in this list - most are reproductions of original portraits and sketches now lost.

FUN FACT: D’Éon was extremely proud of this portrait of her and it was said to be her favourite

6: Chevaliere D’Éon as Minerva by Samuel Hooper - 1773

Ok so this may be a bias but this is one of my favs. Its another romanticised satirical portrait of her and its just so badass.

Here we see D’Éon depicted as Minerva - the Roman goddess of wisdom, warfare and weaving (thats a Xena reference for anyone who wasn’t raised as a tiny lesbian). The shield has the head of feminist icon Medusa on it and according to google translate the text says ‘the hard time Athena has given you differences’ which i feel like is supposed to be the equivalent of god gives his hardest battles to his toughest soldiers kinda thing.

She is wearing the cross of St Louis on her left side while her right side has an exposed breast which we see 57 years later in Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. She has no headwrap this time but the helmet does serve that same purpose, which suggests to me that either this was copied from a sketch of her wearing a headwrap or was modelled on someone else wearing one.

We see here she has a straight nose again altho not as thin and not as pudgy at the end, this feels very similar in facial features to the first portrait we looked at.

Again I think even tho this is a satirical print i don’t believe it should be discounted as part of a canon of D’Éon portraiture as it is just as valuable as ‘realistic’ portraits of her. This aggrandising portrait of her is absolutely propaganda and i love it! After D’Éon published French state secrets and blackmailed Louis 15th this would made her very popular with the English so it is no wonder she was shown in such a positive light. Anyway, if Napoleon can have himself done as Mars why can’t we have a French trans woman as Minerva 🦉💖

7: Chevaliere D’Éon by Angelica Kauffman - 1775(?)

Number 7 here is apparently by Angelica Kauffman. I have only seen one thing say this but stylistically it is at least reminiscent of her work if it isn’t actually hers. D’Éon here has the same haunted eyes that she has painted her own self-portraits with and there are numerous prints that say ‘After Angelica Kauffman’ on them, meaning that she did make a portrait of our dear Chevaliere.

This is one of the few colour portraits i have been able to find of her and is definitely one of the more extravagant portraits of her. We can see the bonnet that has become a staple of D’Éon portraits, but this one is more lavish, being made of patterned fabric with feathers, pearls and a jewel at the front holding it all together. This bonnet gives us a peek of a flat dark hairline which is interesting as most portraits of her have white or grey hair and if we follow the cracked area to the right of her head down we can see curled ringlets gently resting on her neck.

She has a straight nose just like in other portraits but her brows seem less arched and more pointed. She wears large pearl earrings and her dress is blue with gold fringe around the arms just before the bronze-looking sleeves.

Another portrait without her medal!

This portrait also masculinised her giving her a wider face and more square jaw than other portraits have before. I’m unsure if i can personally count this as part of the canon of portraits as while it has some of the main elements, it is still so different. That isn’t to say I don’t enjoy it and am going to entirely discount it cuz i do actually really enjoy it as a portrait cuz we love to see a material gurl but for the purposes of this writing and establishing my own canon on this its just too different

8: Chevaliere D’Éon in her study by Jaques LeRoy - 1775

Portrait number 8 is one of Chevaliere D’Éon in her study, the irl print of which is in the collection of Yale University.

In this we see D’Éon once again without a hat cuz why would she wear a hat in her study. Her face looks more round than the portrait by Angelica Kauffman 2 years prior. Her brows are high and arched and her nose is thin and straight and just looks rather petite, and her hair is also similar to other portraits with the widows peak there but feels more feminine imo. This could just be how LeRoy has engraved the hair but it has a more tumbly quality and its longer and not quite in the same cropped curls as before.

This feels like a very intimate portrait as her clothes look less like a dress or any kind of daywear and more like a dressing gown. We are given no indication of the time of day - we can tell it is some time during the day cuz of the window light but this paired with the robe gives us the feeling she may have stayed up all night writing or she has gone from breakfast straight into writing without getting dressed. She was known to be a prolific writer so it would be unsurprising.

An engraving of an intellectual woman surrounded by books and writing might also have caused a bit of a stir at the time as she would have been expected to be just like other ladies at the time and not concern herself with pesky things like thoughts or opinions.

9: Satirical cartoon of D’Éon published in October 1777

Ok so this is another clearly satirical print but I love it cuz it looks like one of them daft toilet signs where the venue is trying to show the toilet is gender neutral or are trying to be well meaning trans allies and show that ppl of all genders can use this loo but this is the only way they can think to show it.

We can see from this that her nose is again very straight and like her frame it is rather petite. This is also one of the few examples of D’Eon wearing a wig, it seems to largely be in satirical prints that this occurs, as a way to symbolise or perhaps play up her femininity against the dragoons uniform. The widows peak is still present in this too. The eyebrows on the left are more arched and elongated than the right and the shading on the left gives more the idea of make up than shading.

Zoomin in as far as the British Museums website will allow me also show the hint of a breast on the left side with the shading just above the bust-line of the dress.

The imagery used here is one mentioned in reference to D’Éon a fair but - a fan and a sword. Or swapping the sword for the fan. A weird poetic way of claiming there are only to genders but ok lol.

The cross of St. Louis is here on the right as well showing that she is still a decorated veteran.

It is also in this year, 1777, that most cis sources say she began living as a woman full time due to her return to France. This also seems to be one of the more popularly used illustrations of her, which is probably again down to the cisgender lens and gaze cuz cis ppl can’t view us without some sort of visible representation of transition cuz why would we want to focus on all the cool shit she did when we can focus on her transness 🙄

10: Chevaliere D’Éon prints

For number 10 on our list I’m going to do 3 at once as 2 of them were intended to be displayed side-by-side and one is the portrait they are based off. Well the exact two i’ve put here weren’t specifically but the idea was to show her transition so when exhibited they were intended to be ‘before & after’ pictures if u will.

The first is by Jean Baptiste Bradel in 1779 and in this one one we see her in a classic dragoons uniform of the time, including the more accurate helmet with the leopard print trim. Now back in 18th Century leopard print wasn’t considered tacky, in fact quite the opposite - it was a status symbol and showed wealth.

Again we find her with a thin straight nose, thin feminine brows, we can’t see her hair fully but the peek we get at the side shows a similar hairstyle to the others with the side curls. She does have her medal though! It’s safe to say she wouldn’t have sat for this one and it is likely based off previous prints and sketches.

This one is by Francis Howard and is from 1788. It is based on a portrait of her owned by the poet George Keate, who she was a close and “affectionate” friend of. We know this as it is talked about in a letter to her from Keate that is in the Special Collection of Leeds University’s Brotherton Library.

Here we can see a slight widows peak and the rest of her hair is curled but bundled up in the lace bonnet. She has a thin nose again and thin feminine brows. This time she is wearing a low cut dress which shows us her ample bosom, which there are reports of her having. She proudly displays her medal on her dress, which again is more of a status symbol to remind everyone that even though she is a woman she is still a decorated veteran.

This print is based on the Angelica Kauffman portrait, which we say further up, but as you will notice dear reader it looks absolutely bugger all like it! so what gives?

This is the portrait that the above print is clearly based on. We can see everything from the bonnet to the hair, the nose and general facial structure all match that print. But Francis Haward claimed he studied the Angelica Kauffman portrait so this throws a spanner in the works.

This is supposedly D’Éon at 25 years old which would either date this in 1753 or it was done after the fact as an approximation of what she looked like.

We know that depictions of D’Éon at this age exist as there is the account of Louis XV having a portrait of her commissioned in pastels by Maurice Quentin De La Tour to send to Empress Elizabeth to show what her new lady-in-waiting would look like. However the pastel portrait has never been found! As mysterious as much in D’Éon’s life!

If this is the portrait that Keate owned then it can’t be her at 25 as she didn’t receive the cross of St. Louis until she was 35. Could Kauffman have painted 2 radically different portraits? It is a possibility as there are some smaller stylistic similarities. If we were to compare to the Kauffman portrait of Queen Charlotte (well it’s a photo of a portrait but we can work with that) we can see the similarities in how Kauffman paints lace, I’d also suggest that the style the noses of both portraits are done are similar as well as how the bridge leads up into the brow as well as the way the eyes are painted on both.

We know that D’Éon knew Queen Charlotte as she was sent to England to influence her and spy on her. There were also rumours of the two being lovers and that D’Éon was even George IV’s biological father! If Kauffman was painting Queen Charlotte as well as other royalty and nobility (which she very much did) then D’Éon would certainly want to be painted by her.

It could be that the first portrait by Kauffman was just a copy of the La Tour pastel portrait as she was travelling around Europe learning more of her craft and could have come across the sketch during her travels. If so, then I’m sure she would have relished the chance to then do her own portrait of D’Éon when she encountered her years later in England.

If we follow this theory then the first portrait’s date of 1775 could be incorrect, or it could have been started much earlier and finished around then as some artists do. The second portrait doesn’t have a date with it other than the 18th Century, so let’s come up with a rough ballpark:

Angelica Kauffman moved to England in 1765 and appears in the Royal Academy's first catalogue in 1769, cementing her as one of the more popular artists in England at the time. Charlotte had been Queen 4 years by the time Kauffman moved here and D’Éon had been here 3 years. By 1771 the public prints of D’Éon in dresses were beginning to circulate and her fame was rising to the point where she was being talked about in most major newspapers.

Prints of Queen Charlotte by Thomas Burke (the same Thomas Burke who did the 2nd print on our list and was a regular engraver for Kauffman) labelled “after Angelica Kauffman” were made in 1772, so her portrait of Queen Charlotte must have been between 1761 and 1771. By 1771 Chevaliere D’Éon would have been 43.

D’Éon certainly does not look old and she can’t have looked too dissimilar to this or Kauffman wouldn’t have painted her like this, there is only so much flattery you can do in a painting like this.

So at the latest this must have been painted around 1771 at the height of D’Éon’s fame and the earliest it could have been painted, if it was commissioned by George Keate, would be when Keate met Kauffman in 1768 when the Royal Academy was formed at which time D’Eon would have been 40.

Another reason I wouldn’t date this any later than 1771 is that the satirical print of Kauffman The Paintress of the Macaroni’s is clearly a reference to her painting D’Eon.

This gives us a 3 year period where D’Éon would have sat for the portrait. If D’Éon was still close with Queen Charlotte or even just a part of the same circle as her at the time (which she undoubtedly would have been) then we can imagine Queen Charlotte seeing D’Éon’s portrait and wanting one for herself, potentially commissioning Kauffman in 1771, the year the Royal Academy were given space in the royal palace of Somerset House.

This, to me, is the most plausible theory to pin this painting down in the canon of D’Éon portraiture.

What have we learned so far??

Soooo, by lookin at these 10 portraits what have we learned?

While there is clearly no consensus on what she looked like with some portraits like the first one attributed to Angelica Kauffman being very leftfield, we can count the similarities here.

D’Éon, at least up til her 40s, had a round face with short-ish curled hair with a hat or bonnet to cover it. She had a thin nose with quite thin brows. She also had a small but protruding chin. She preferred to be pictured with her medal and often preferred to wear her dragon's uniform until she was threatened with being arrested for not wearing a dress. She also had a fairly petite frame.

What about the very obvious breasts in some of the paintings? Surely this was before HRT was invented? Well actually no it isn’t as estrogen treatments have existed in medicine dating back quite a way, particularly in ancient china. She could have been taking a concoction of herbs to help transition. Or she could have been intersex and had something to the effect of Klinefelter syndrome.

In much the same way many cisgender historians say ‘we don’t know what their internal sense of gender was’ I would also say we don’t know that she didn’t have tits. There is a report of her having breasts at her time of death and I see no reason why we shouldn’t believe that in conjunction with the portraits that very clearly show her having breasts.

The British Museum describes the print by Francis Haward as a “print which goes to such lengths to emphasise D'Éon's femininity that it has lost any resemblance to the original sitter.” - this is a deeply transmisogynistic narrative as it ultimately says any trans woman that doesn’t just look like a man in a dress can’t be real. This is a big example of the Cis Gaze as this isn’t based on anything other than that view of what cis people believe a trans woman should look like, especially in the 18th century. Do we question if the armada portraits of Elizabeth I are an accurate representation? Or Marie Antoinette? Do we question if Canova’s Venus Victrix is much of a likeness of Pauline Borghese? (ok that last one maybe, but the others we don’t).

As I mentioned earlier, portraits are propaganda of the time and the point of getting ur portrait painted was to look fancy and glorified. Especially if u had smth to be glorified for like idk being a decorated national treasure. These interpretations are made by cis ppl by cis institutions thru a cis lens interpreted for other cis ppl as a curiosity or an oddity. hell the british museum might as well have a ‘freak show’ sign next to work about her as that’s the vibe they are carrying on with.

So now we have built ourselves a canon for what she surely looked like we can examine a few further portraits to decide how these would fit and whether they are just transmisogynistic propaganda.

11. Chevaliere D’Éon - print from portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds - 1782

I can’t find the original painting of this but this print does appear in The Strange Career of Chevaliere D’Éon de Beaumont: Minister Plenipotentiary from France to Great Britain in 1763 by Captain John Buchan Tefler. It is attributed to Sir Joshua Reynolds, which would make sense as Reynolds was a close friend of Kauffman at the Royal Academy, and it is dated 1782 which is a whole decade after when the last portrait on this list was. This would make D’Éon 53.

And Reynolds is determined to show it. We don’t see a petite feminine woman in front of us now, we see someone who has been depicted more as a pantomime dame or some sort of miss havisham. Her nose isn’t as small as in others and is now large and hooked, her chin remains the same but her face does look less round yet fuller. Her brows are still small and we can see rouge clearly on her cheeks, which is giving her a flushed look.

She has similar hair to previous portraits just more ~volumous~ and she has a bonnet or veil on her head which gives her further volume and length.

D’Éon is seen here wearing a more conservative dress which was probably seen as more appropriate for a woman of 53 in the 18th century. Her cleavage has been covered and this is probably another way the artist was telling viewers that she has aged. Her body shape does still give us the suggestion of her having breasts though.

Does this portrait fit our canon? Yes and no (soz but this is where things get tricky from here on in).

She ticks all the boxes we made before except for those nose, which could easily have been broken from all the exhibition matches she engaged in.

How then does it look so different? Could we chalk that up to having a decade go by? No, I think we have to consider the artist’s bias and style in this as much as anything cuz like i look at this painting and i’m not being given the impression this is a woman who could hold her own when fencing and i think thats intentional as she was still living in France and would have been expected to have given that up and settled into being the grande dame that was expected of her as opposed to in England where she was much more free.

12: Chevalière D’Éon - Louis Jacques Cathelin - 1786

So this engraving by Jacques Cathelin from 1786 is, according to the British Museum “The first which offers an accurate representation of the Chevalier d'Eon's life as a woman from late 1777 until [wrong pronoun] death in 1810. It is entirely devoid of satirical intent and presents the Chevalier as a homely middle-aged woman in lace cap, crucifix and gown, with the Cross of Saint-Louis pinned to the bodice.” - Now this rings alarm bells for me as what they are ultimately sayin here is any portraits of her that make her look like a cis woman or not like a non-passing trans woman are full of “satirical intent” which is hella transmisogynistic there hen.

Cathelin was the King’s own engraver, that king being Louis XVI, and the portrait was done while D’Éon was still living in France. This could be based off a now lost portrait by Joseph Ducreux (yes of meme fame) which I can see as it would fit into his style.

This contains the typical stylistic things we see in most post-transition portraits of her such as the bonnet, the widow’s peak, protruding chin and her medal. This looks younger than the previous portrait by Joshua Reynolds, which does leave me wondering if Reynold’s portrait has that “satirical intent” where he has aged her up and made her look a bit like a pantomime hag.

Her head seems rounder, which could be her putting weight on, and her nose is much more of a ‘roman’ nose than in previous portraits which again we could say is down to her nose getting broken in an exhibition match or smth

We can again see from this that she isn’t particularly flat chested, which i think is part of that “satirical intent” the British Museum are on about cuz god forbid an intersex or trans woman have anything close to tits before Christine Jorgensen. D’Éon’s dress also has similar sleeves to the Angelica Kauffman, a style that would have been popular at the time. So unlike The Ugly Duchess painting, D’Éon is being shown as quite fashionable and in a favourable light.

Again I’m unsure if I personally would count this as part of a canon of D’Éon portraits, especially after that British Museum interpretation.

13. Chevaliere D’Éon by Richard Cosway - 1787 - engraving by Thomas A E Chambars

This engraving by Thomas A E Chambars is based on a painting by D’Éon’s friend and fellow freemason Richard Cosway. Cosway was also a Royal Academian (is that what they were called? Fuck knows) with Joshua Reynolds and Angelica Kauffman.

Given they were friends it is likely that D’Éon sat for the original portrait, and i do think it would have been a painting as the style inferred by Chambars in this engraving matches up with the style of Conway’s paintings. He was known for his miniatures and painted other figures D’Éon would have known such as George IV and Madame Du Barry.

So does this bear the hallmarks of a D’Éon portrait as we’ve discussed it so far?

Well we can see her signature bonnet with a widows peak poking out. Her cleavage is covered again denoting age but she is still wearing her medal. Her nose is straight and thin like in prior portraits so if her nose was broken in an exhibition match then she must have sat for a portrait before that happened.

We again see her having a rounded face but again to a more masculineised proportion. Perhaps her face was changing with age and with that aging a change in hormones that would have changed how she looked, but this is all speculation as it does fit into the canon that we are creating here and i doubt Cosway would want to do his friend and fellow freemason dirty with an wholly inaccurate portrait.

14. Chevaliere D’Éon - George Dance - 1793

This portrait is by the architect George Dance who settled into making more portraits in the last 30 or so years of his life. He was a member of the Royal Academy and had been friends with Angelica Kauffman before they were both there, so its no surprise that he wanted to draw D’Éon.

Dance has included many of the things we have come to expect of a portrait of D’Éon such as the outfit - black frock with a white shawl and a white bonnet. He has not forgotten her medal! We can see her hair poking out at the side and a small part coming out of the top of the bonnet.

Her nose is straight again which at this point would throw out any broken nose theory and makes me wonder if it was added to some portraits by people as they may have considered it less feminine trait to give her to hint that they believe she is just a man in a dress (enough with the transmisogyny guys we get it 🤮). She is known to have sat for this portrait so we can consider this a relatively accurate likeness of what D’Éon looked like at the age of 65.

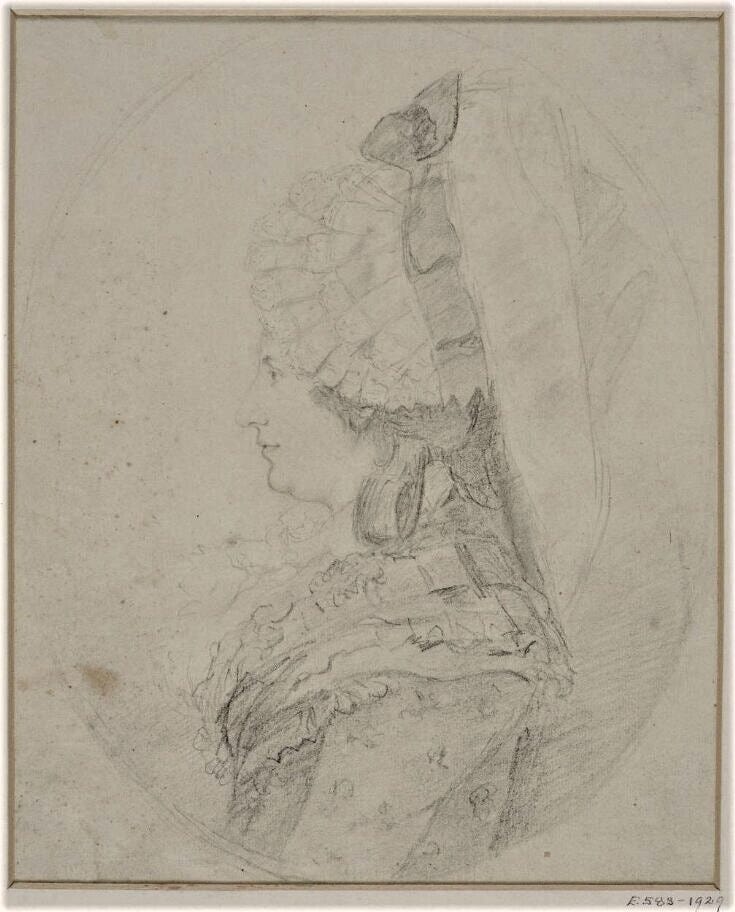

This had a preparatory drawing that is held by the V&A and we can see her with a younger look, but that might be down to the lack of detail in the sketch. Her hair is looped at the side and her dress has flowers on it, something we don’t see in the end product, perhaps as it would have been considered improper as a woman at her age was expected to be dressed and portrayed in a certain way.

Her medal is barely visible and is reduced to just a few crossing lines to give the impression to the artist that it was there. She has the straight nose and small round chin, followed closely by the bit of weight we can see she has put on.

This is the only colour portrait that not only still exists, but has a preparatory sketch available as well! What a rarity! Because of that I would be inclined to interpret this as the most accurate portrait as we have evidence that she definitely sat for this and we get 2 for the price of 1 lol

I’d count this as being part of the cannon of D’Éon portraits as it’s not too different to the engraving based on the Richard Cosway portrait. The fact that there is also a preparatory sketch tells us that she was sitting for this at lest the once, so any differences between this and the Cosway depiction of her are likely more down to artistic style than anything else.

15. Chevaliere D'Éon - Thomas Stewart - 1792 (‘discovered’ in 2012)

This is perhaps the most famous painting of her and its housed in the National Portrait Gallery here in the UK. Its based on a painting by Jean-Laurent Mosnier from 1791 which is pretty similar but relies on a darker and colder colour palette as opposed to the warmer one we see here.

Her bonnet has been swapped out for a hat with large feathers (potentially ostrich although that was extremely expensive!) which at this point would have been more fashionable than a bonnet so I don’t blame her for wanting to keep up with the women’s fashions of the time as who wouldn’t want to look fashionable in their portrait.

Her cleavage is covered by a white lace shawl as it is in other portraits and we can see more of her now naturally white hair but no view of a widows peak. She has her medal but this time also sports a ribbon on her hat signifying the revolution. This would have been controversial at the time as she would be expected to pick a side, yet here she is hedging her bets.

Her nose is straight here but is wider than in previous portraits. It does not look too different from her nose in the Angelica Kauffman portrait from 1775 and while her face on first glance seems more masculinised, this could be more the androgyny of ageing as D’Éon is in her 60s here. If she was intersex or taking some form of estrogen then that mixture of hormones would certainly add to that.

She still has a small protruding chin although here it looks more angular, but again that could be due to ageing and sagging around the jaws and neck.

You will notice she is devoid of pearls much like the last few portraits have been (its ok u can scroll back to go check). Pearls were a symbol of virginity in portraits and she hasn’t been depicted with any since Joshua Reynolds portrait of her - this could be simply down to her not wearing any or it could be intentional on the part of the artists to not want to link her with virginal debutantes of the time as older women were not treated well in art at all. D’Éon also has more colour about her complexion in the same way Reynolds painted her, whether this is just to compliment the colour palette or to again symbolise smth about her that is not complimentary is anyones guess

This portrait was only identified as D’Éon just over a decade ago (2012) supposedly by Paul Crane but i’ve been struggling to find anything about this and even the National Portrait Gallery don’t know him and couldn’t give me more info so it looks like the main way it might have been identified as D’Éon is once again the cis idea of what a ‘man in a dress’ in 18th century would look like and thats the only one of them they can name

16. Death Mask of Chevaliere D'Eon - Charles Turner - 1810

So this is the final portrait of D’Éon that was done in her lifetime and it is her death mask.

Upon her death in May 1810 the landlady she lodged with was preparing her body (as was traditional at the time, doctors were rarely involved) and began to strip her to wash her body and discovered her genitalia was not that expected of a cis woman. She called for a doctor who also brought an artist with him to sketch her.

The doctor performed an inspection of D’Éon’s body and an autopsy. He described her as having a perfectly formed penis and full breasts, the former of which was sketched by Charles Turner. I have seen the sketch in the online catalogue of a museum and it is horrifying that it is something that can be viewed and gawked at online 😱😭 I won’t name the museum here but jaysus do they need to take it off their catalogue

This death mask portrait is at least a little more respectful 🙄 here we see a hooked nose like the one in Joshua Reynolds portrait of her. We see her with sunken eyes as well which is likely a sign of being in her 80s. D’Éon’s face shape is not too different from the Thomas Stewart portrait and is less round than in previous portraits and has a more square jawline.

If we compare this to other profile portraits of her the chin would be similar to the George Dance portrait of her, albeit a little more saggy and protruding as if it was a witchy halloween prosthetic.

Charles Turner has chosen not to draw her hair here which could be an active choice to leave it out or he just didn’t bother or she didn’t have any at this point - bear in mind that she hadn’t been fencing after being stabbed in the chest in 1796 and was paralysed from the waist down so hadn’t been seen in public since 1806 and. The last portrait had been almost 20 years prior to her death so we can expect plenty of changes that would come with age potentially including hair loss.

So is this the most accurate portrait of her? I’m not sure. Logic would dictate that a death mask would be the most accurate but we can’t discount the last 46 years of portraits of her.

Conclusion

So whats the one conclusion i can bring this number to? Well none. There isn’t one conclusion and as usual u are welcome to make up ur own mind but what we can do is establish a canon so we can look at her thru a trans lens rather than thru the cis gaze.

So here are some of the things i discussed above that i think makes a D’Éon portrait:

Headwrap/Bonnet/Hat/Helmet

Roundish Face

Widows Peak hairline

Arched, thin eyebrows

Straight nose - until around 1780s but after that we could accept a hooked broken nose

A protruding chin

Cross of St Louis

Plain black (if in etchings, colour is fine in paintings) dress or dragoons uniform

Lace coverin her cleavage after 1780s

So which ones are canon portraits of D’Éon?

Well despite my gripin and moanin, all of them.

When i started writing this i was so determined to establish a canon and discover what she actually looked like but now not so much all cuz of one really important detail - she was a spy!

If our beloved James Bond can look different every couple of movies then why the hell can’t an 18th century trans woman who is also a spy not look different.

As i pointed out earlier looking at her thru a trans lens is important and while i don’t particularly like the transmisogyny used in the way cis ppl have identified portraits as her, it has its uses. From a trans view we can use that transmisogyny of cis historians to be able to find and see portraits of D’Éon but also from the position of a spy we can see how useful it might be that while people are looking for someone they have decided is a man in a dress, they aren’t looking for the woman who wouldn’t look out of place amongst other beautiful portraits of women in any stately home, cuz where D’Éon is concerned i think we can truly say Nobody Does It Better